Back to summary

Ep 2 - The Fervor of Lucha Libre

It’s been less than 24 hours since I arrived in Mexico City. I discover lucha libre—halfway between sport and theater—by heading to Arena México. Before that, I meet photographer Jeoffrey Guillemard, who had just spent several days documenting the daily life of “El Gallo Francés.” Then it’s my turn to meet “Lady Drago” in a gym on the outskirts of the capital during a training session.

I. Diving into Arena Mexico

I still haven’t gone back to Alex’s place, my French-Mexican friend. No—I chose instead to head to a massive arena where people of all ages and social backgrounds scream, cheer, and let loose in a wild atmosphere: lucha libre. Inside Arena Mexico, all eyes converge on a raised central square, framed by three ropes—the ring. On some nights, especially Tuesdays, up to 15,000 aficionados gather in a venue often considered the Mecca of wrestling in its Mexican form.

© PR.ednasantos

I’m not alone in soaking up this popular, folkloric spectacle. Earlier in the day, I met Javier, a 32-year-old Mexican entrepreneur. A chance encounter? Not really. On previous trips, I learned how to use the Couchsurfing app to connect with locals who are always welcoming, sometimes inspiring. Javier is no exception. He enjoys meeting travelers and showing them the beauty of his country.

Living in Aguascalientes, north of Mexico City, he runs a private school. “Education is good business—future generations will always need education to climb the social ladder,” he tells me confidently. That’s one way to look at it. Using the app to organize group activities, it felt only natural for him to suggest that I experience the fervor of lucha libre. It’s Tuesday—the opportunity is too good to pass up, especially with Mexicans.

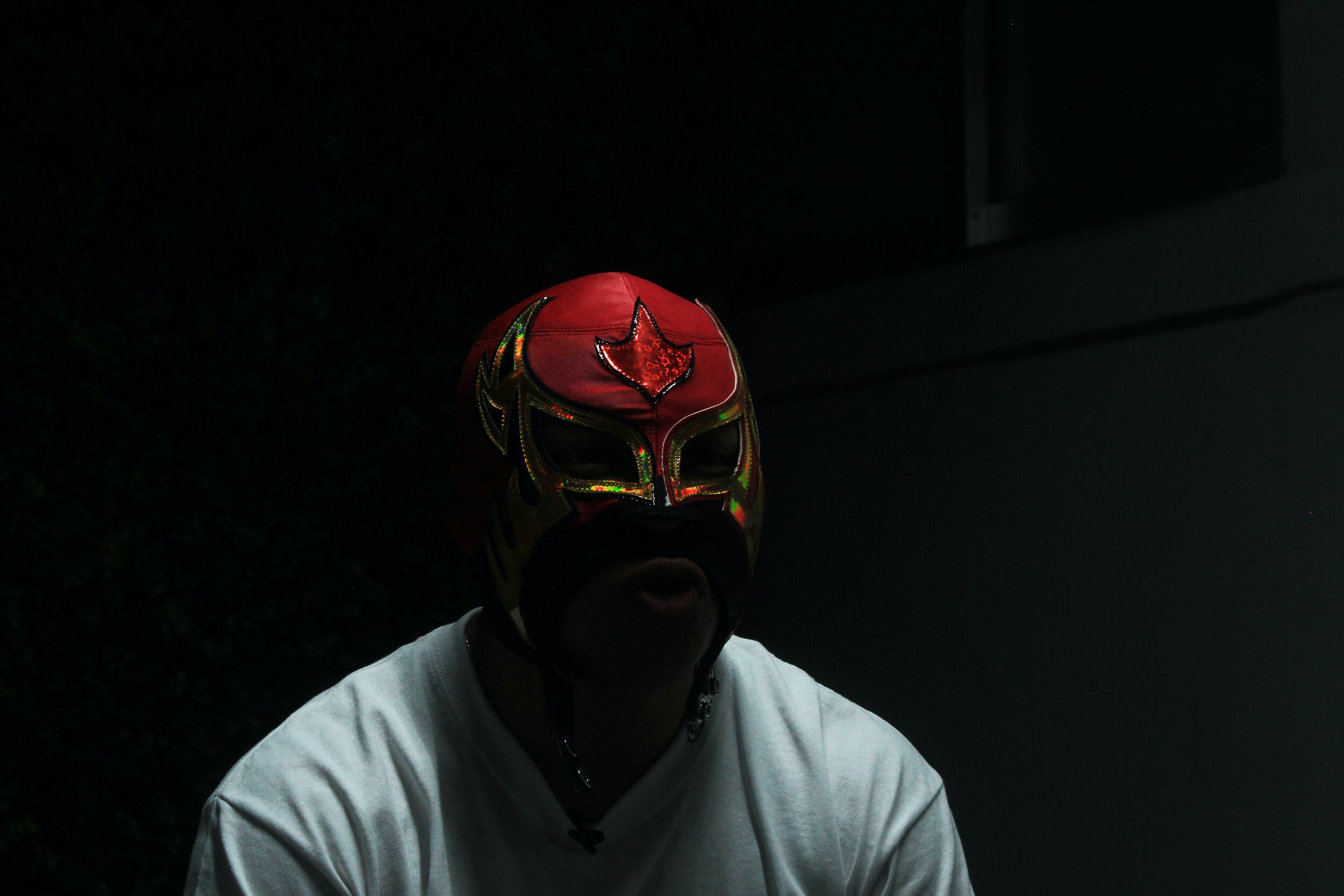

Halfway between sport and theater, lucha libre is a carefully choreographed performance mastered by wrestlers elevated to the rank of superheroes. Each one wears a personalized outfit with one essential element: the mask, which must never be lost. Behind those masks are true enthusiasts—men with bulging muscles or round bellies, women in skin-tight tights, and dwarfs hungry for greatness.

The origins and rules of lucha libre

© Secreteria de Cultura Ciudad de México

According to the ever-reliable Wikipedia, lucha libre was introduced to Mexico during the French occupation in 1863. Thanks, Napoleon III. Over time, it has become a culture in its own right, bringing together thousands of fans. Among roughly a hundred active professionals, about ten—the most famous—have the honor of fighting in Arena Mexico. Some manage to live off their passion in a country where the average monthly salary hovers around €670.

While the rules are similar to those of American wrestling, the style is more aerial and spectacular. It’s hard to explain the rules in detail—they’re vague and flexible. One essential aspect to understand is the existence of a perpetual struggle between good and evil: the técnicos (the good guys) versus the rudos (the bad guys).

Another fundamental element of lucha libre is the mask, a symbol of life. Having it torn off is the worst humiliation a luchador can experience during their career. Getting slapped? Fine. Getting your ass kicked? Fine. Getting thrown into the crowd? Fine. But losing your mask and revealing your identity? N-E-V-E-R.

Matches are decided by two winning rounds. Suspense being what it is, they usually go to three. The técnicos play by the rules; the rudos don’t, really. A referee does his best to maintain order, with little success. Sometimes he gets slapped—it’s deserved.

II. My Meeting with Photographer Jeoffrey Guillemard

Nothing is straightforward in Mexico City: getting around, meeting up, knowing what’s allowed and what’s not. Good to know—it’s nearly impossible to enter Arena Mexico with a camera (cell phones are still allowed). The venue’s owners want to control their image as much as possible. For reasons known only to them.

Being a well-known, talented photographer doesn’t necessarily help. Jeoffrey Guillemard knows this all too well. This French photographer, based in Mexico since 2014, has worked with prestigious outlets such as Le Monde, Libération, and Rolling Stone. I met him in a café near Alameda Park on the day I arrived. Along with journalist Rémi Vorano, he had just spent several days following the daily life of “El Gallo Francés,” an amateur wrestler who embarked on a crazy adventure: making a name for himself in Mexico. While Jeoffrey and Rémi had complete freedom to shoot in less prestigious arenas, collaborating with Arena Mexico turned into a logistical nightmare—one they chose to abandon, at least for the time being.

My camera, a FujiFilm X100F, may look harmless, but the security guard refuses to let me in. A Mexican man who’s with me offers to stash my bag in his car. We lose a few minutes—long enough to miss the first match between female wrestlers. We arrive just in time to catch a dwarfs’ match, three on three.

The atmosphere of the matches

Dwarfs’ matches—how to put it… less aerial, but downright burlesque. Slaps fly left and right, echoing throughout the arena. They charge like mules and use their thighs to smother their opponents. Clever. Sometimes they jump in to support other matches between wrestlers, adding a whole new dimension to the fight. The atmosphere is electric. I don’t yet understand all the crowd’s expressions, but I doubt they’re words of love. “Chinga tu madre!” meaning “Your mother’s a ****!” for example. Poetic.

In the stands, the creativity of the insults defies comprehension. The top prize goes to whoever shouts the biggest piece of nonsense. Around the ring, it’s a bingo of clichés: nacho vendors, pints of beer flowing freely, cheerleaders shaking it to welcome the wrestlers, giant screens to see the action up close… total immersion.

I leave Arena Mexico completely drained, my head as big as a watermelon—but with sparkling eyes and a grin from ear to ear. Slightly dazed from jet lag. I want to share this moment. To bear witness, to find an original angle. The place of women in this ruthless world? Jeoffrey just happened to give me the contact of a professional wrestler: Lady Drago.

III. The Daily Life of a Professional Wrestler

Barely out of Arena Mexico, with the help of photographer Jeoffrey Guillemard, I message Lady Drago, explaining my approach. I get straight to the point: I’d like to meet her during a training session and then attend one of her matches. Good news—she’s interested and available. One detail, though: this young woman, about five foot one, trains on the top floor of a gym located outside the city, in a “less-than-recommendable” neighborhood.

No matter. She suggests I come two days later, late morning. The timing is perfect before I hit the road again. A bit of research to prepare my interview on her Facebook profile—nearly 5,000 friends: Lady Drago posing with other masked wrestlers here, Lady Drago sharing drawings of herself made by her community there, not to mention selfies in her various costumes.

Two days later. I was right to take precautions and book an Uber more than an hour in advance. On the road, traffic is chaotic. But what could possibly push us to change our behavior—at least temporarily? Pedestrians wearing masks offer the first hint of an answer. An invisible and threatening passenger, COVID-19, is about to arrive. Our mobility will soon be affected.

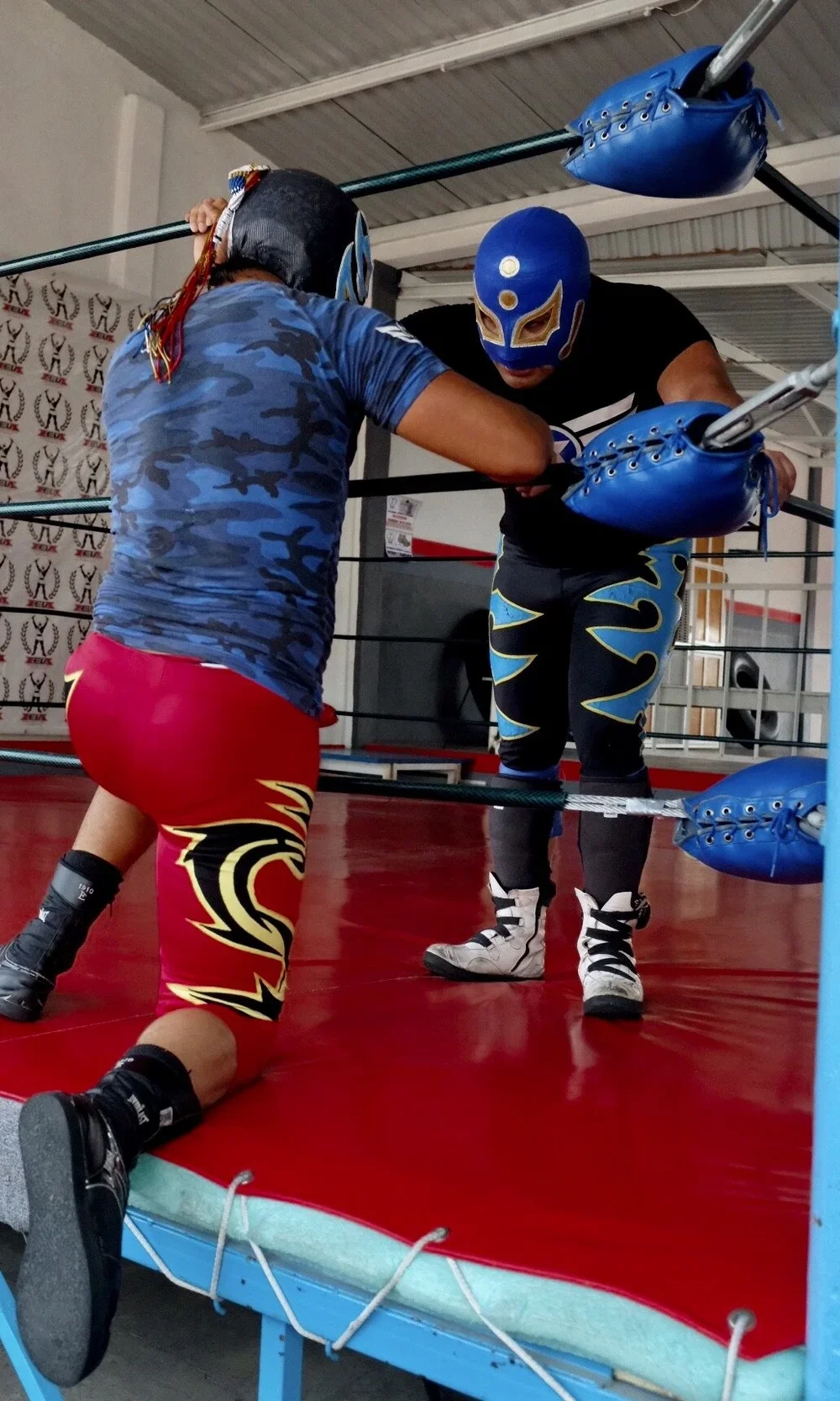

Ten minutes late, I arrive at the gym: Zeus School Gym. Lady Drago and three wrestlers have already started training. No time to waste—I ask them to act as if I’m not there so I can focus on photography first.

There’s no magic formula: to become a professional wrestler, regular training is essential. Three times a week, in two-hour sessions, Lady Drago runs through sequences designed to make her movements fluid and as close to reality as possible. While the blows are deliberately exaggerated, the risk of physical injury is very real.

Lady Drago, who chose the dragon as a symbol of resilience, can attest to that—she was kept away from the arenas for a year and a half after a bad fall. Lucha libre is often a family affair. Lady Drago’s father was known as the Celestial Dragon, while her brother trains alongside her.

The wrestlers talk during training, give each other advice, and signal when someone lands badly. Facial expressions—personalized dances, superhero-like attitudes—are practiced over and over again. Breath control is also essential to avoid faltering during performances.

“I hope you had a good time, Sébastien,” Lady Drago exclaims with a smile. “Lucha libre gives me a lot of adrenaline, especially when I perform in front of an audience. That’s actually what drives me forward.” I ask whether she’s a técnica or a ruda. “Both,” she replies with a smile. “It all depends on what the arena needs. Right now I fight at Arena Tepito and Arena López Mateos. Sometimes with women, most often in mixed matches, because my coach trained me for that.”

So is there a difference between male and female wrestlers, especially in a country with a reputation for machismo? “No, not in my opinion. We follow the same path: we make a name for ourselves in gyms and street shows before catching the attention of the bigger arenas.”

And what does she think of the increasingly visible feminist movement in the country following a new wave of femicides? Does she want to be one of its spokespeople? “Those questions aren’t for me. I’m not a feminist,” she says flatly.

Uppercut—end of the interview. I head back to central Mexico City. I can think all I want about a potential article, but it’s hard to find an original, offbeat angle. Watching Lady Drago fight the following week might help me see things more clearly… Unfortunately, the show is canceled. The project falls through—too bad. I choose to focus on the rest of my journey instead.

Sébastien Roux

Cover photo © Carlos Ramirez